This is part 4 of 4 where I asked debut authors whose novels I included in my Library Journal column to share their inspiration-- the books or authors which are their favorite scariest reads.

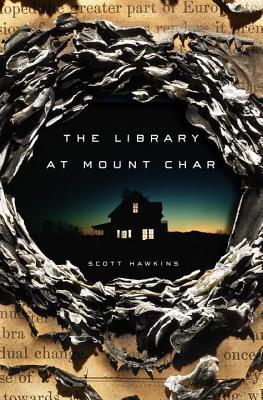

Today I am featuring Scott Hawkins author of the fantastic The Library at Mount Char.

Today I am featuring Scott Hawkins author of the fantastic The Library at Mount Char.

Red Dragon by Thomas Harris

by Scott Hawkins

Like a lot of people in 1991, I came to the writing of Thomas Harris via the “Based on the Novel By” credit at the beginning of the movie Silence of the Lambs. I’d been vaguely aware of his work since 1977—I remember the Black Sunday movie tie-in was everywhere for a while—but the first time I actually read anything of his was in the wake of the movie.

Silence of the Lambs, awesome though it is, is not my favorite Harris novel. I think the predecessor, Red Dragon, is just as well-written and slightly stronger in terms of story. In this post I’d like to talk a little bit about why I love Harris in general and that book in particular.

To start with, Hannibal Lecter , arguably the best villain of the twentieth century, is introduced in Red Dragon. But Lecter is just the crown jewel of a large horde—or one of them, at least. In writing this, I gave serious thought to proposing the villain of Red Dragon, Francis Dolarhyde, as the superior bad guy. In the end I think it was Lecter by a nose, but consider that for a moment—a character so finely wrought that you have to think about whether or not that character is superior to Hannibal Lecter. That’s not a debate you’re going to have very often. Thomas Harris’s novels are exquisite.

To start with, Harris’s books epitomize what a thriller should be—high stakes contests between bad (if somewhat sympathetic) and good (if slightly flawed) protagonists. They’re page-turners, virtually flawless in pace and plot. That’s certainly been remarked on before, but it’s worth mentioning again.

What I see mentioned less often is the stellar level of craftsmanship he brings to the writing. For instance, his dialogue is always a window to character, and often dryly funny in a way that didn’t make it into the films. Here’s a snippet from Silence between Jack Crawford and Dr. Danielson. Dr. Danielson is not a fan of the FBI:

“[…] I know how thorough Johns Hopkins is. You’ve got cases like that, I’m sure of it. Surgical addicts apply every place surgery’s performed. It’s no reflection on the institution or the legitimate patients. You think nuts don’t apply to the FBI? We get ’em all the time. A man in a Moe hairpiece applied in St. Louis last week. He had a bazooka, two rockets, and a bearskin shako in his golf bag.” “Did you hire him?”

Harris also has an unusual gift for crafting details. To a greater or lesser degree, every writer has an internal eye for scene. A case might be made that learning to write is about training yourself to see with that eye—which details matter? Which don’t? The very best practitioners can come close to the platonic ideal—only those things which matter are noted, but nothing is missed. The first time I really understood that notion was when I read the following paragraph from Red Dragon in which Hannibal Lecter speaks to investigator Will Graham for the first time:

“I’ve read the papers. I can’t clip them. They won’t let me have scissors, of course. Sometimes they threaten me with loss of books, you know. I wouldn’t want them to think I was dwelling on anything morbid.” He laughed. Dr. Lecter has small white teeth. “You want to know how he’s choosing them, don’t you?”

For me, the sentence “Dr. Lecter has small white teeth” is a near-perfect example of how details may elevate a scene. On first read through, it’s a little jarring—why the hell do we care about teeth? It doesn’t have any obvious bearing on what is being said. But when you think about it, it’s perfectly natural, just the sort of minor point that the eye lights on in real-life conversations. Better still, Harris gives us this without a two-paragraph detour designed to showcase his vocabulary. It’s six basic words that convey a clear visual image. Last--and most important--if you take a moment to think about what Lecter does with those teeth, it’s creepy as all hell.

But perhaps the signature magnificence of Harris’s novels is his characters—the monsters in particular. To my mind the thing that makes Francis Dolarhyde (Red Dragon), Jame Gumb ( Silence of the Lambs) and Michael Lander (Black Sunday) so chilling is their essential humanity. Harris first established the ferocity of the Red Dragon using the details of his most recent crime scene—among other things, the killer placed mirrors over the eyes of the dead children, then propped them up to watch. That creepy enough for you? If not, just wait. But shortly thereafter he follows up the atrocity with a good-sized island of pathos in the text. That, to my mind, is what really sets off Dolarhyde as a charcter. After you’re done learning about his formative years, it’s hard not to feel at least a little compassion for the monster.

The villains of Black Sunday and Silence of the Lambs were similarly forsaken. Michael Lander, the homicidal pilot of Black Sunday, was tortured by the Vietnamese as a POW. He returned home in disgrace only to find home wasn’t there anymore—in his absence, his wife had remarried. Jame Gumb’s own mother couldn’t even be bothered to spell his name right. To be clear, Harris never, ever implies that these misfortunes justify blowing up the Superbowl (Black Sunday) or making skin suits (Lambs). But it’s not hard to see where these bad guys might feel a bit hard done by.

Harris, I think, sees the world through a compassionate lens. I’d emphasize the distinction between compassion and willful blindness here--he’s not a bleeding heart. There is room for evil in his world view. After the movie became a mega-hit, Lecter got a tragic background similar to that of Lander and Dolarhyde. The sixth finger on his left hand vanished. But once upon a time, the 20th century’s signature bad guy was simply a psychiatrist who simply chose to be bad. He liked to cook, and he collected clippings of church collapses that resulted in fatalities.

If you’re up for a deep dive into the darkest nooks and crannies of the human heart, you can’t do a whole lot better than Thomas Harris, and Red Dragon is his very best.

Last and least, I hope you’ll excuse a brief but shameless plug: if you like dark thrillers where the bad guys still have a sliver of humanity and the protagonists aren’t angels, you might also check out my own debut, The Library at Mount Char.

Happy Halloween!

No comments:

Post a Comment