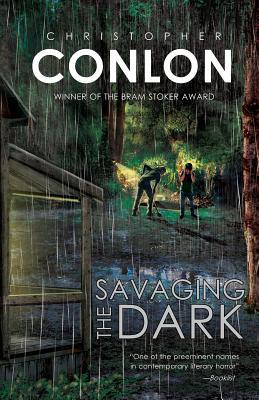

Back in May, I posted here about the Booklist Top 10 best reviewed horror of the year. On their list was one of my favorite horror authors for public library collections-- Christopher Conlon and his most recent novel, Savaging the Dark.

At my request, Conlon shared his thoughts on the novel for you-- my public librarian audience.

But first, a little about Conlon. He is best known as the editor of the Bram Stoker Award-winning Richard Matheson tribute anthology He Is Legend, which was a selection of the Science Fiction Book Club and which has appeared in multiple foreign translations. He is the author of several novels, including the Stoker Award finalists Midnight on Mourn Street and A Matrix of Angels, as well as many books of stories and poems. Among his most recent titles are When They Came Back: A Horror Story, featuring photographs by Roberta Lannes-Sealey, and Wild Tracks: Uncollected Writings 1985-2014. A former Peace Corps volunteer, Conlon holds an M.A. in American Literature from the University of Maryland. Condon lives in the Washington, D.C. area. Visit him online at http://christopherconlon.com.

A big thanks to Conlon for sharing his thoughts below. And again, I highly recommend his novels for all public library horror collections.

The Horror of Savaging the Dark

by Christopher Conlon

copyright © 2015 by Christopher Conlon

Being as vain and self-absorbed as most other writers I know—well, all other writers I know—I was naturally delighted to discover that my novel Savaging the Dark had made Booklist’s recent “Top Ten Horror: 2015” list, right up there with the likes of Stephen King and David Cronenberg. Such recognition, in this case totally unexpected, is wonderful to receive—which is why I know I run the risk of churlishness in admitting that I was also just a tad uncomfortable with this particular accolade.

It has to do with that word “horror.”

Now, let me say at the outset that I am a lifelong lover of horror. The writer who first made me fall in love with fiction as a child was Edgar Allan Poe, whose stories of psychological turmoil and terror spoke deeply to me, growing up as I did in a chaotic atmosphere dominated by two wildly alcoholic parents. For years I was obsessed with late-night reruns of The Twilight Zone; through them I discovered the dark and frightening worlds of Richard Matheson, Charles Beaumont, and of course Rod Serling, all of whom became favorites whose books I read and collected avidly (and still do). There was also Robert Bloch, discovered through Hitchcock’s Psycho; Arch Oboler, located through audio cassettes I mail-ordered of his seminal radio show Lights Out; and many others—Ray Bradbury, H.P. Lovecraft, Harlan Ellison, the list goes on—first spotted through the many second-hand paperback anthologies I would buy two-for-a-quarter at the local thrift shop.

Not all of this reading was strictly horror, of course—each of these writers skirted genres, and I was just as happy reading their mysteries and fantasies and science-fiction tales as I was their more straightforwardly bloodcurdling efforts. But all of them spent a great deal of time on, we might say, the darker side of the street, where I was always eager to join them.

As I got older and went to college my tastes widened and deepened considerably, but I still seemed to prefer writers of a shadowy bent. I went through a Conrad phase, enthralled by Heart of Darkness and “The Beast in the Jungle.” For a time the Southern Gothics of McCullers, Welty, Capote, and Tennessee Williams became my literary soul food. Still later, I binge-read such notably un-sunny writers as Toni Morrison and Joyce Carol Oates.

Perhaps as a result of this, my own writing has never been known for its happy-go-lucky, Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm qualities. My characters, invariably psychologically scarred and emotionally haunted, make their ways as best they can through worlds of death, abuse, sorrow, and misery, searching for a kind of home few of them ever really had.

Savaging the Dark is such a story. It focuses on the relationship between Mona Straw, a thirty-something middle school teacher, and her eleven-year-old pupil Connor Blue—a relationship that grows emotionally intense for both of them and, eventually, sexual.

The depiction of such a transgressive bond is hardly unique, of course—Lolita comes immediately to mind, though Savaging the Dark is a very different kind of narrative from Nabokov’s great satirical classic. Still, my novel does seem to have touched a nerve in some readers, and not necessarily in a good way.

What’s most interesting to me is that the protests as to the nature of this novel have come entirely from within the horror world—a world with which I have been identified for some time, not always comfortably. While the novel has received some good notices in horror publications, there have been horror reviewers, well-known and respected, who have completely refused to read the book, or, having read the first chapter or two, refused to finish it. One likened the novel to “kiddie porn”; another admitted he “just couldn’t do it.” Some horror markets which have covered previous books of mine very favorably have simply ignored their review copies of Savaging the Dark without comment.

Of course, one sympathizes with readers’ potential sensitivities; all the talk lately about placing “trigger warnings” on books sold on college campuses indicates that these can be real issues for some individuals. Still, the people I’m talking about are horror reviewers, who every day read graphic depictions of the worst kind of sadistic torture and mutilation and murder, and give it rave notices when it comes bylined by an author like, say, Richard Laymon. Indeed, there is often a gleeful quality in such writing, and in horror readers’ responses to it. Whether it’s a Tales of the Crypt comic-book story in which body parts are merrily strewn about or devoured for laughs, or a novel like Bret Easton Ellis’s American Psycho, in which a starving rat is dispatched up a woman’s vagina (among other memorable scenes), horror readers often seem to delight in the outrageous, the disgusting, the transgressive. But something about Savaging the Dark appears to have alienated some in the horror audience. Ironically, the novel has been saved largely by mainstream readers and librarians—exactly those one might imagine would be least attracted to a story like this one.

Let it be said here and now that Savaging the Dark bears the same resemblance to “kiddie porn” as Lolita, or Sally Mann’s famous photographs of her children—that is to say, exactly none. My story is about the techniques and consequences of psychological manipulation and abuse; the entire arc of the narrative is downbeat, grim, and tragic. Nothing in the book is played for laughs, and nothing is designed in any way to be titillating. It is, I hope, a disturbing story, a vivid and memorable one. That’s what I set out to write.

And that, I have come to suspect, is exactly the problem. Too often the horror genre doesn’t take its own horror seriously. Instead the grotesque is treated in a nudge-wink fashion which may be appropriate to comic books but which surely isn’t for novels written by and for supposedly mature grown-ups. And it’s precisely this attitude, I think—this juvenile perspective, this giggly approach to psychosis, sadism, monstrousness—that causes horror as a genre to be dismissed by many as disreputable trash, which, if we are to be honest, a lot of it is. Savaging the Dark has no connection to such material, a fact which mainstream readers seem to realize—hence the gratifying accolades from non-horror outlets.

So is Savaging the Dark a horror novel? Perhaps. It’s certainly fine with me if Booklist believes so, especially since they think so highly of it.

What it is not, however, is a product of the horror genre.

I find it sad that such a distinction has to be made, but there it is.

In the end, Savaging the Dark is simply, I think, a novel, as Heart of Darkness is a novel, or indeed Lolita. Readers sensitive to the issues it presents should probably not pick it up. But self-described horror fans who find themselves resistant to the book, or too afraid to read it, may want to reflect on just what they believe the word “horror” really means.

No comments:

Post a Comment